My Photos 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Extracts from "The Vanished Fleet of the Sydney Coastline" by Max Gleeson, a great read.

Built by the firm of H. Robb of Leith Scotland, Bombo departed on her delivery voyage under the command of the veteran seaman Captain Manning on February 11th, 1930. In the last six years, Manning had brought six new vessels out to Australia, the last being the vehicular ferry Kalang. In the early nineteen thirties, the Daily Telegraph featured a daily column called, "About ships and the men who know them". The feature reported that: "Manning was the Mate of the barque Balmoral in 1876, when she brought out the organ now in the Great hall of the Sydney University. The captain is always cheerful and has a laugh which starts in the back of his white beard and almost makes the bulkheads rattle".

The Bombo

encountered heavy seas in the English Channel near Ushant off the coast of France. So bad was the weather, the crew could not make their way safely to the forecastle head and had to spend one night aft in the mess room. The ship called in at Port Said, then anchored off Aden to adjust her engines before the long run across the Indian Ocean to Sydney via the Torres Strait. Bombo arrived in Sydney Harbour on April 23rd and although the vessel was five days ahead of schedule, the crew were very low on rations.The vessel took up her role for her new owners freighting blue metal from the Kiama harbour to Sydney. In December 1935, State Quarries sold their assets to Quarries Pty Ltd and the Bombo and her crew transferred over to the new company. The vessel averaged five trips a week and appeared to run incident free up to the start of the Second World War.

With the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in September 1939, the Navy set about converting approximately thirty-five coasters into auxiliary minesweepers. This fleet was made up mainly of old trawlers, colliers and small wooden cargo vessels.

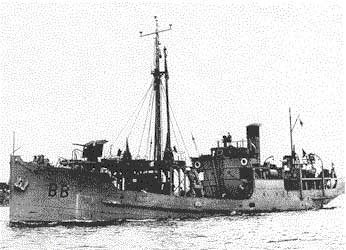

Bombo

was requisitioned for naval service in February 1941 and fitted with a

single twelve-pound gun, which was mounted on the forecastle head. Also

installed, abreast of the foremast were two Oerlikons machine guns. Commissioned

in Sydney in May 1941, under the command of Lieutenant Arthur S. Codling, RANR(S),

she operated between Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart as an auxiliary minesweeper

until November 1943. Bombo was then converted into a stores carrier and

left Sydney in February 1944 and spent the next eighteen months in the Darwin

and Northern Australian area. During wartime the vessel had a complement of

thirty-five men and on many occasions she participated in gunnery practice with

the Darwin defence forces by towing targets outside Darwin Harbour. Included in

her ports of call over that period of time where the remote Islands of New Year,

West Montalivet, Peron and North Goulburn. On September 11th, 1945, the steamer

participated in the occupation of Koepang, Netherlands Timor by the Australian

Army. With the end of hostilities, Bombo sailed from Darwin for the last

time in late November 1945; however, she was not returned to her owners until

July 1947.

Bombo

was requisitioned for naval service in February 1941 and fitted with a

single twelve-pound gun, which was mounted on the forecastle head. Also

installed, abreast of the foremast were two Oerlikons machine guns. Commissioned

in Sydney in May 1941, under the command of Lieutenant Arthur S. Codling, RANR(S),

she operated between Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart as an auxiliary minesweeper

until November 1943. Bombo was then converted into a stores carrier and

left Sydney in February 1944 and spent the next eighteen months in the Darwin

and Northern Australian area. During wartime the vessel had a complement of

thirty-five men and on many occasions she participated in gunnery practice with

the Darwin defence forces by towing targets outside Darwin Harbour. Included in

her ports of call over that period of time where the remote Islands of New Year,

West Montalivet, Peron and North Goulburn. On September 11th, 1945, the steamer

participated in the occupation of Koepang, Netherlands Timor by the Australian

Army. With the end of hostilities, Bombo sailed from Darwin for the last

time in late November 1945; however, she was not returned to her owners until

July 1947.

Upon the vessels resumption of her normal duties, Captain Arthur Bell once again took command of the Bombo. During the war years, Bell had commanded the veteran Antarctic exploration ship, Wyatt Earp, which had been renamed Wongala after her intake into the Navy. Wongala served the duration of the war in the examination service at Port Adelaide before operating as a guard ship at Whyalla. The captain's association with the town of Kiama went back to April 1910, as first mate of the London Mission Society's vessel, John Williams II. That vessel had embarked on a voyage to raise funds for the various island missions in the South Pacific and had called in at Kiama for the purpose of an exhibition.

In September 1947, Captain Bell brought the Bombo into Kiama Harbour for the first time since February 1941, where once again she became a familiar sight running between Sydney and the south coast.

On December 29th, 1948, Bombo grounded on the Kiama bar. The vessel suffered slight damage to her keel and during her repairs, her owners decided to bring forward her annual survey. The second week of 1949 saw the Bombo complete what was to be her last survey. The vessel was repaired and once again resumed her duties, in a seaworthy condition.

After an eight and a half-hour trip down from Blackwattle Bay in Sydney, the Bombo arrived at Kiama at 9.30 am on the morning of February 22nd, 1949. Loading began immediately, Captain Bell supervising the procedure. He was very particular about the loading of the cargo, always filling the number two hold to its capacity, then terminating the loading of the number one hold when the water level reached the vessel's Plimsoll mark. Upon the completion of the loading, Bell's intention was to move the vessel to the adjacent wharf, owned by the Illawarra Steamship Co, to pick up some machinery for Sydney. However, due to the wind the captain had difficulty bringing the vessel along side the wharf and decided to leave the shipment until the return trip. Shouting his intensions to those on the jetty, about the freight, Bell slowly eased the Bombo out of Kiama Harbour with another cargo of crushed blue metal for the Sydney road system. At 11.55 am, she passed through the tiny harbour entrance, leaving the quiet seaside town for the very last time. Ahead lay a fifty-five nautical mile voyage to Sydney Harbour which they were expected to complete at approximately eight o'clock that night.

The Bombo's crew consisted of fourteen men, several being veterans who saw war service in the merchant navy. The rest of the hands were made up of men with considerable experience in the local coasters. Holding the position of Second Engineer was John Stevenson. The sixty-year-old had served in the Royal Navy in the First World War, followed by the Merchant Marine in the second conflict. In the years preceding the war he was employed as chief engineer on several of the United Nation vessel's, which took relief supplies to war torn China. Within a fortnight, Stevenson planned to resign his position on the Bombo, for a trip back to Scotland and no doubt was counting the days as the trip drew near.

At twenty-seven years of age, able seamen Laurence Lucey was by far the youngest member of the Bombo's crew. Lucey had joined the Merchant marine ten years earlier and had survived the Dunkirk campaign, ferrying solders back to England. He was also a crewmember of the passenger ship, Macdhui when she was bombed and sunk by Japanese aircraft off Port Moresby in June 1942.

Also on the vessel were the seasoned veteran and former crewmember and survivor of the colliers Myola and Tuggerah, Thorvald Thomsen. The coming month of May would mark the thirtieth anniversary since the able seaman had escaped in a lifeboat from the foundering Tuggerah and with the other survivors rowed towards the safety of Port Hacking. Thomsen, born in Denmark, in 1891, was now fifty-seven years old and one could only surmise at the man's thoughts in the many times he passed over the grave of the Tuggerah in the preceding years.

The Bombo made her way out to her usual northbound course to a point several miles off the coast. Sea conditions had changed for the worse since their voyage down the coast earlier that day. Shortly after passing the Five Islands off Port Kembla, weather conditions began to deteriorate even further as a result of a stronger south-easterly front passing up the coast. The clear skies prevalent at the start of the voyage had been replaced by dark skies matching the same colour of the rolling ocean. Heavy rain with strong wind squalls followed the ship up the coast, partly obliterating the outline of the Illawarra escarpment. With the seas striking the Bombo on the stem starboard quarter, the vessel became difficult to steer and a number of occasions broached into the white cap covered sea.

By the time Bombo had reached the point abeam of Stanwell Park, the ship was under onslaught from the elements, her decks constantly awash from the huge seas. In spite of the conditions, the vessel was behaving reasonably well. Captain Bell and "his" ship had faced similar conditions on many occasions throughout the years without incident, nevertheless he was concerned at the strong buffeting the vessel was receiving.

In the next hour the gale began to intensify. The Bombo plodded on, her speed being greatly reduced by the circumstances. At 4.00 PM, when five miles north of Stanwell Park, the vessel was struck by a huge wave which crashed right over the ship, causing her to list heavily to port. As she did, the blue metal in the holds dislodged and shifted with the list to the port side of the holds. The crew braced themselves as tons of water streamed its way off the deck and the vessel slowly began to right itself. Gradually the Bombo corrected, leaning over to starboard at first and then resuming a slight list to port. Realising the ship may be swamped if another wave struck the vessel; Captain Bell immediately turned her nose into the swell and sent word to the engine room to reduce speed. Bell sent a man up forward to inspect the hatches and minutes later the seaman reaffirmed the captain's fears about the shifting cargo. In these circumstances, Bell was not going to take any chances, deciding to continue the south course, hopefully to the shelter of Port Kembla Harbour. There they planned to square the cargo up and after staying the night, leave for Sydney the following morning.

Resting in his bunk, Thorvald Thomsen felt the ship turn around. He went up on deck to find out what had taken place and was told by another crewmember they were heading back to Port Kembla to tidy up the cargo. Thomsen estimated the list to be approximately 5 degrees and was quite surprised the captain had elected to turn the ship about. Thomsen's mind went back to a similar incident several months earlier, when the Bombo was under the command of a relief skipper, as Captain Bell was on vacation. When the vessel developed a comparable list to the present one, the captain turned the ship into the sea and sent the crew up forward to detach the hatches and trim the cargo. On this occasion the manoeuvre was successful, however in the present sea conditions, Thomsen was well aware, that to remove the hatch covers would be fatal.

Against the gale, with her engines just turning over, the crippled Bombo began the eighteen nautical mile voyage back to Port Kembla Harbour. Initially the incident was looked upon by the crew as an inconvenience more than anything. An hour after the incident the list had remained stable. At 5.00 PM, Captain Bell sent a message via the radio station at La Perouse, to the foreman of the Bombo's discharge gang at Blackwattle Bay in Sydney Harbour. It read: "Cancel gang tonight. hove to. OK master".

Ever so slowly the ship forged her way towards the sheltered waters of the harbour. There was no thought amongst the crew of the vessel of not reaching Port Kembla. Almost five hours had passed since the Bombo had swung about and still there was little change in the degree of the list. At around 9.00 PM when the ship was approximately five miles from her destination, fireman Michael Fitzsimmons went down to the boiler room to take his turn stoking the fires. The fireman had three fires to attend and in the next fifty-five minutes, Fitzsimmons carried out his work, replenishing the first fire and then the second.

Meanwhile, on duty at the Maritime Services Board signal station at Port Kembla was Arthur Treble. At 9.30 PM, Treble sighted a vessel north east of his station and began to signal her with Aldis lamp. The Bombo answered the signalman's call; however, owing to the apparent rolling of the vessel it proved impossible to read. Treble continued to keep the mystery vessel under observation with his binoculars until she came about three miles north of Port Kembla. The time was exactly 10 minutes to 10.00 PM. In less than ten minutes the Bombo would be on the ocean floor. Treble again signalled the vessel in the darkness, asking for her identification. "Bombo" came the reply, "sheltering". Treble signalled, "message received" and the Bombo acknowledged. The signalman then turned his attention briefly away from the sea and recorded the incident in his log.

The Bombo was now less than a quarter of an hours steaming from the safety of Port Kembla. With the shovel in his hand, Fitzsimmons moved to the third fire, however, there was' no doubt in the fireman's mind the list was increasing and increasing dramatically. Fitzsimmons would later comment to the press about his last few moments in the boiler room: "I didn't wait to finish that fire, but dropped the shovel and said to myself. 'Mike, it's time for you to go. The Fireman scampered up the boiler room ladder to the deck just in time to hear the captain yell, all hands on deck and man the starboard lifeboat". Together with five other crewmembers, Fitzsimmons tried to lower the lifeboat, however they were unsuccessful due to the extreme angle of the deck. All knew the end was very near. It was then Fitzsimmons realised he wasn't wearing a lifejacket. Together with able seaman Charlie Barhen, he jumped to the lower deck to secure their lifejackets and were shortly joined by another five crewmembers. All seven men lined the high starboard handrail, awaiting the inevitable. Charlie Barhen turned to his mate and said, "are you ready Mick?" "Yes, let's go", replied Fitzsimmons. Their jump triggered off a chain reaction as the remainder of the crew followed their shipmates into the black ocean. The men endeavoured to put as much distance between then and the sinking ship. Swimming to a safe distance, Fitzsimmons turned around, just in time to see Captain Bell jump from the bridge at the last moment, as the Bombo rolled over and began to sink bottom up. Within two minutes the steamer was gone.

The captain made his way over to the rest of the crew, which were now clinging to two planks that had floated off the ship. "Keep together boys", he shouted as he regained his breath. A count of heads revealed ten men out of fourteen had escaped from the vessel, the survivors believing the others had gone down with the ship. Resting on the planks the men discussed their chances of survival and their best course of action under the circumstances. Fitzsimmons asked Captain Bell if he managed to get a message away? "Unfortunately no," replied Bell, just a few minutes previously, I had morse with the station that we were alright and proceeding to anchor". The survivors then knew there was no chance of any immediate help. It was every man for himself.

Signalman Treble finished his written report in the log and once again looked towards the open sea with his binoculars to see if the vessel was going to enter Port Kembla Harbour. However, he saw no sight of the Bombo and tragically assumed she had taken shelter in Wollongong harbour.

Together with the wind and currents the survivors began to be carried north. After a short space of time, the Chief Officer, Henry Stringer, decided to make an attempt to reach the shore. Stringer, a strong swimmer could see a red light in the direction of Bulli, however the distance was far greater than it appeared. Telling the captain to keep the men together, he set off towards the shore, hoping to bring back a launch to rescue his shipmates. Charles Barhen also followed him. Stringer's body would be washed ashore at Corrimal beach at 11.00 am the next morning and Barhen's body would never be recovered.

Throughout the night, under atrocious conditions, the remaining members of the Bombo's crew grasped the vessel's broken woodwork and prayed their chief officer had made the safety of the shore. As the hours passed, gradually the conversation stopped as each mans respiratory rate was slowed by the cold water. With the loss of heat from their bodies, came the uncontrollable shivering, loss of co-ordination and numbness.

Around 5.00 am the first streaks of daylight appeared over the grey horizon. Captain Bell and Bill Cunningham had slowly succumbed to the cold during the night; their bodies still supported by their life jackets could be seen floating nearby. Those crew still alive, included Emie Norris, John Stevenson, Laurence Lucy, Edward Nagle, Mick Fittsimmons and Thorvald Thomsen.

Through the sea mist, Emic Norris sighted the dim outline of a beach several miles away. He suggested it was time to make a move and "every man strike out for himself towards the shore". Fitzsimmons, later stated to the press: We decided to split up, as we were afraid we might claw one another if we started to drown". All agreed, as one by one at intervals of fifteen minutes the men left the planks which had supported them throughout the long night. Fitzsimmons, a suntanned, thick heavyset man of forty-nine years was the third man off after Nagle and Thomsen. By his own admission, he was not a good swimmer, but by swimming the breaststroke he was able to keep steadily going towards the beach. One hour after striking out, Fitzsimmons passed the two crewmembers who had left the floating debris before him. With little or no strength left, the two men were completely exhausted after their eight-hour ordeal in the sea. There were a few words of encouragement to each other and little else. This was survival of the fittest in its rawest form.

Thorvald Thomsen continued his journey to the shore. He also passed a shipmate on the way. The crewman was donkeyman Edward Nagle, who had set out just before him and was not wearing a life jacket. Thomsen sighted him clinging to a hatch cover, however, a little while later he noticed the cover floating without him.

At approximately 10.00 am, twelve hours after the sinking, Thomsen was sighted just outside the breaker line off Bulli Beach. Paddling a surf ski, the beach inspector, Percy Ford had rushed a reel to nearby Shark Bay and against mountainous seas, battled his way out to the Bombo's survivor. Thomsen was picked up by several huge waves, turned over and almost lost his life jacket. He later stated to the press: "It was not until I struck the breakers that I feared I would not live to reach the beach". Thomsen was in danger of being swept upon rocks when Ford reached him. The lifesaver was unable to drag Thomsen aboard, but he had sufficient strength to hold on to the end of the ski while Ford paddled in the direction of the beach. Thomsen was carried to the Bulli Kiosk, where he was then conveyed to Bulli Hospital suffering from shock and exposure.

At approximately the same time, Michael Fitzsimmons stumbled ashore, unseen at Woonona Beach and made his way up to a nearby road. There he saw a baker's truck passing and after flagging it down, said to the driver: "Mate, I've just been shipwrecked".

Once news of the shipwreck became known the search for any more survivors triggered into full swing. Two R.A.A.F Catalinas departed from Rathmines and began an extensive examination of the coastline from Port Kembla to Port Hacking. Conditions for flying were atrocious. An object, which was thought to be a body was, sighted a mile east of Stanwell Park and a marker was dropped, however, when the aircraft turned around for another sweep, neither the object nor the marker could be seen. Shortly after the pilot radioed and was granted permission to return, reporting: "Coastal search impossible, heavy rain, low cloud along the cliffs, big seas and visibility almost nil".

Despite the swiftness in which the airforce had joined in the search for the missing men, the Bombo's owners where sluggish in organising suitable vessels to scan the ocean for any survivors. It was not until the midafternoon that the first vessels got underway. The tug Warung left Port Kembla Harbour to join in the search, but it was Albert Bamett, Skipper of the trawler City Gull, which came across the first corpse. Bamett left the trawler's wheel and lowered himself over the side to hitch grappling irons to the body. A pair of binoculars on the unfortunate man indicated it was Captain Bell. He was still wearing his cap and his wristwatch had stopped at 10. 15. More bodies were sighted by the City Gull, but their closeness to shore made it far to risky to take the trawler in to recover them. Two ambulances and about fifty people, including relatives of some of the missing men, waited in the rain at Wollongong Harbour for the City Gull to return. There were distressing scenes on the dock, as the vessels return marked the end of any hope of finding more of the Bombo's crew alive. A further search was carried out the following day, but the bodies of the ten missing men were never recovered.

Recovering from their beds in Bulli hospital, both Thomsen and Fitzsimmons relayed their story of the sinking and how they had survived the night. Thomsen mentioned to the press his escape from the collier Tuggerah, off Marley beach a generation before. He was shortly joined by his wife who caught the train down to the south coast to be with her husband. Thomsen was released several days later fully recovered and from that point in time, the fate of the man who survived the wrecks of two "sixty milers", thirty years apart, is unknown.

The relatives of Captain Bell were critical of rescue measures taken by the ship's owners, Quarries Pty Ltd. The captain's son, Norman Bell stated to the press: "I think a rescue ship should have been sent out immediately. We have been kept very much in the dark about the whole thing and know nothing about the sinking, except my father's body had been identified at Wollongong'. In the light of the many years in which Captain Bell had served the company, Norman Bell's criticism appeared justified.

At the Court of Marine Inquiry into the loss of the Bombo, both Thomsen and Fitzsimmons agreed that it was the shifting of the blue metal, which had caused the initial list. Thomsen told the court, the end had come so quick; not allowing several men resting in their bunks to escape before the ship rolled over. On the last typed page of the inquiry, stating Thomsen's evidence into the incident and written in his own handwriting, was a note. It read: 'I think Captain Bell was a good seaman. The captain could not have done more than he did under the circumstances. Thorvald Thomsen 3rd March, 1949".

The Inquiry handed down its decision on April 27th, 1949 and found: "The ship was properly loaded and further finds that the ship was handled in a seamen like manner by the master. It also finds there is no evidence of which any findings can be made to show the actual cause of the foundering of the ship".

The first thing one notices when visiting the Bombo's wreck site, is her closeness to her destination - Port Kembla harbour. Like many of the wrecks contained in this book, this is also the case. Anchored over these wrecks on a warm summer's day, it is sometimes very hard to visualise that men could have lost their lives out here. However, the sea has many moods.

Lying upside down, on sand, in one hundred feet (30 metres) of water, the Bombo has collapsed amidships. At the stem her large four bladed propeller dominates the area, her rudder having since fallen off. The hull has split open around the engine room, revealing the ship's boiler. Looking at the boiler, which has one of the fire doors open, one cannot help but think of fireman Fitzsimmons, dropping the shovel and making his way to the top deck.

There is sufficient room for a diver to swim into the main hold. Through the broken hull, shafts of light illuminate the sandy bottom. In the darkness above, thousands of Nannygai line what was once the bottom. Her fatal cargo of blue metal lies buried beneath the sand with only the occasional Stingray or Wobbegong shark marking the spot.

Due to her closeness to the harbour, water visibility around the wreck can be poor, however clear water often sweeps the area and in the right conditions the Bombo is a very enjoyable and interesting dive.

| BOMBO |

| BUILT, LEITH SCOTLAND, 1930. |

| LOST OFF PORT KEMBLA HARBOUR, FEBRUARY 22ND, 1949. |

| LENGTH 154'3" x 30'1" x 12'0". |

| TONNAGE 540 GROSS. 282 NETT. |

| SURVIVORS |

| THORVALD THOMSEN ABLE SEAMAN |

| MICHAEL FITZSIMMONS FIREMAN |

| LOST |

| ARTHUR BELL CAPTAIN |

| HENRY STRINGER CHIEF OFFICER |

| PERCY CARROLL CHIEF ENGINEER |

| JOHN STEVENSON SECOND ENGINEER |

| EDWARD NAGLE DONKEYMAN |

| ERNEST NORRIS FIREMAN |

| THOMAS BELVOIR FIREMAN |

| CHARLES BARHEN ABLE SEAMAN |

| WILLIAM CUNNINGHAM ABLE SEAMAN |

| LAURENCE LUCEY ABLE SEAMAN |

| JAMES GORDON RIDDELL STEWARD |

| ARTHUR LIGHTBURN COOK |

EXTRACT FROM 'THE SOUTH COAST TIMES' THURSDAY FEBRUARY 24th 1949

Ship Capsizes Off Wollongong

Twelve Drowned

Two survivors came ashore at Bulli on Wednesday morning after being ten hours in the water.

The two survivors are: Michael Fitzsimmons (48) fireman, of Napier street, North Sydney, and Thorvald Thomson (57) also a fireman.

The body of another member of the crew was washed ashore north of Corrimal and Mr. A. Barnett, in his trawler Pacific Gull, recovered a second body believed to be that of the captain. Fitzsimmons was little the worse for his experience, but Thomson was suffering badly from exposure and was taken to Bulli Hospital for treatment.

The Bombo, a steel vessel of 640 tons was built in 1930 especially for carrying blue metal from Kiama to Sydney. On Tuesday she left Kiama shortly before noon for Sydney, a trip which usually takes about eight hours. She was carrying about 600 tons of metal, slightly less than a full load. A graphic story of the trip was told by Fitzsimmons; who claimed that the cause of the sinking was the shifting of the ship's cargo. He said after leaving Kiama they sailed the usual course but about 5 pm, when about 5 miles off Stanwell Park he noticed the ship listing to port. He said he heard the Captain A. R. Bell tell the chief engineer he was going to turn back and to keep the engines going slowly to keep steerage way on the ship.

They continued southward until about 9.30 pm. when, some four or five miles north east of Wollongong lighthouse, he heard that the Captain had informed the second engineer he proposed to drop anchor off Port Kembla until daylight. Fitzsimmons said he noticed the list was getting worse and than heard the Captain' shout "All hands on deck and lower the starboard lifeboat". "I tried to assist two sailors to lower the boat" said Fitzsimmons, ship began to list more so we grabbed the lifebuoys and jumped. He said the captain and seven others followed them and no more, than no more than two minutes later the ship turned over on her port side and sank.

Fitzsimmons said the captain told them to keep together and they commenced swimming towards the beach, six of them clinging to two pieces of timber. Another man who was swimming weakly was helped to this board. "After paddling for some hours we became very tired," said Fitzsimmons, "and then we just hung onto the timber." The floated around until about 4 o'clock when the beach came into site and they recommenced to paddle. One man pointed out the plank might be dangerous in the surf, so one by one they left the plank and made for the shore. He said he managed to struggle ashore where he took off his lifebelt. He made towards a house where he saw a bread carter, Mr. Hobbs, of Hubbards bakery, who gave an overcoat and took him to Bulli police station.

Throughout yesterday a close watch was kept on the beaches and an aerial search was carried out.

Mr. E. F. Reid, of Wollongong and South Coast Aviation Services, with Mr. Brian Crump, as observer, made a two hour search in one of the companies tiger moth planes. Members of the Woonona Surf Club joined in the search with a lifeboat. Heavy seas and drizzling rain made the task more difficult for searchers. Late yesterday afternoon a Catalina search plane dropped flares over several objects floating in the water off Coldale.

Owing to very heavy seas, however, launches and boats were unable to put out to investigate the wreckage and pieces of similar were washed ashore at many beaches, but only a lifebuoy found near Bulli beach has been actually identified as coming from the Bombo. Police and citizens have maintained watching squads on cliffs and beaches between Cronulla and Wollongong during the day.

Fitzsimmons was in a state of collapse when he arrived at the Bulli Police station with Hobbs and had to be carried into the station. He refused to go to hospital and declined a suggestion that he should have a sleep. He was provided with a meal at the home of Sgt P. Kennedy, Bulli station sergeant. Sgt. Kennedy also gave him socks, shoes, and clothing.